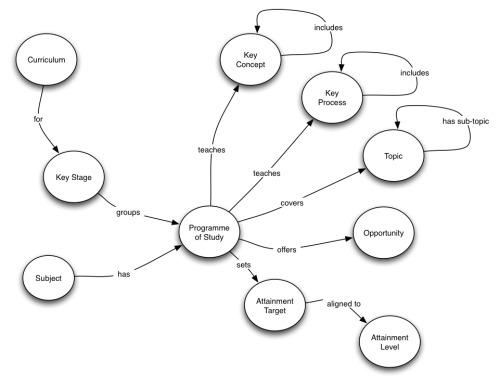

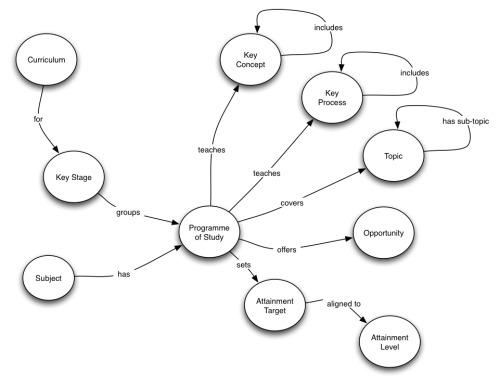

As promised, a picture and explanation of the Curriculum Ontology. There’s still a lot more to do, but (constructive) comments are very welcome.

Curriculum

A Curriculum groups Key Stages – so, in England, we have the Primary Curriculum, which is used at Key Stage One and Two, and the Secondary Curriculum, used at Key Stage Three and Four.

Key Stage

I’m defining a Key Stage as a stage of a formal education system which represents a level of knowledge, behaviour and skills at which a pupil should be able to perform. This is commonly matched to an age range. So, in England, Key Stage Three is nominally for pupils aged eleven to fourteen (aka Years Seven to Nine), and Key Stage Four is for fourteen to sixteen year olds (Year Ten and Eleven).

Subject

Subjects. The things that most people are familiar with – the subjects. English, Maths, History etc. So far, so straight forward. But, as you progress through an education system, although you might study the same subjects, what you learn within those subjects will change. Sometimes it’s a more advanced version of a topic you’ve already covered, and sometimes it’s something completely new.

So, we need to make sure that, for a given subject, we can give you the right material – and this will depend, amongst other things, on which stage of the curriculum you’re at. This is achieved through Programmes of Study.

Programme of Study

A Programme of Study defines what is taught for a particular subject at a particular Key Stage. It’s the difference between Maths at KS3 and KS4. But luckily, things are a little more defined than this. What are the actual differences? What is a Programme of Study made up of? We can break down a Programme of Study into the following things – Key Concepts, Key Processes, Topics, Opportunities, and Attainment Targets. Let’s take a look at each one to understand what they mean.

Key Concepts

What is a Key Concept? And how does it differ from a Topic? or from a ‘Key Process’ (whatever that is…)?

Let’s look at some examples.

In the Programme of Study for Geography at Key Stage Three, some of the Key Concepts are:

– An understanding of the physical and human characteristics of real places.

– Appreciating different scales – from personal and local, to national, international and global.

– Understanding the significance of interdependence in change, at all scales.

For Science, also at KS3:

– Critically analysing and evaluating evidence from observations and experiments.

– Examining the ethical and moral implications of using and applying science.

– Sharing developments and common understanding across disciplines and boundaries.

So, to me it seems to be an idea, or a principle of the subject, that can be taught. It’s not a specific topic, but it’s something that could crop up in several topics.

And, indeed, the National Curriculum website says that a Key Concept is something that “underpins the study” of a particular subject – “Pupils need to understand these concepts in order to deepen and broaden their knowledge, skills and understanding”.

Key Processes

Key Processes seem to be more about skills and abilities that students should be taught. So, for instance:

In Geography, KS3:

– Pupils should be able to ask geographical questions, thinking critically, constructively and creatively.

– They should be able to identify bias, opinion and abuse of evidence in sources, when investigating issues.

– They should be able to select and use fieldwork tools and techniques appropriately, safely and efficiently.

Science will be quite similar, so let’s try English at KS3:

– Pupils should be able to use a range of ways to structure and organise their speech to support their purposes and guide the listener.

– They should be able to infer and deduce meanings, recognising the writers’ intentions.

– They should be able to maintain consistent points of view in fiction and non-fiction writing.

So, similar but different to a Key Concept – I’ve defined a Key Process as “a process, skill or behaviour that a pupil should learn in the context of a subject at a particular key stage, in order to be able to make progress”.

Topics

On the National Curriculum website, the Programmes of Study define Key Concepts and Key Processes, but then talk about the ‘range and content’ of a subject. At first glance, it’s what we’d commonly call the topics that a student actually learns about. For example:

In Maths, KS3:

– Applications of ratio and proportion.

– Linear equations, formulae, expressions and identities.

– Units, compound measures and conversions

It can be a bit more complex than this, though. In English at KS3, the range and content section has topics, but they are then broken down in to more general guidance, presumably allowing teachers more freedom, for instance, to select books and plays which match the characteristics given. For instance (paraphrasing here…):

– Speaking and Listening: The range of purposes should include describing, instructing, narrating, explaining, justifying, persuading, entertaining, hypothesising; and exploring, shaping and expressing ideas, feelings and opinions.

– Reading: The texts chosen should be of high quality, interesting and engaging, challenging. The range should include works selected from a defined list of pre-twentieth-century English writers, and at least one play by Shakespeare.

Something similar is also seen in the Programme of Study for History. So it’s more than just the topics – the National Curriculum website says that the ‘range and content’ “outlines the breadth of the subject on which teachers should draw when teaching the key concepts and key processes”.

I’ve defined it, for now, as a concept or principle that should be covered by teachers when teaching pupils. But it might need a bit more detail. It feels like it could be broken down into actual topics and a more wooly ‘guidance’ (or something!), but that might be going too far. Perhaps just a better name than ‘Topics’ would do.

Opportunities

Each Programme of Study lists a number of ‘Curriculum Opportunities’, which can be used as springboards for inspiration on how to deliver the material to students. These are things which are “integral to their learning and which enhance their engagement with the concepts, processes and content of the subject.” So they are can be seen as activities which would help facilitate learning, just as the topics and content would help teach the Key Concepts and Processes. Some examples:

The curriculum should provide opportunities for pupils to:

– experiment with a range of approaches, produce different outcomes and play with language (English, KS3)

– watch live performances in the theatre wherever possible to appreciate how action, character, atmosphere, tension and themes are conveyed (English, KS3)

– use creativity and innovation in science, and appreciate their importance in enterprise (Science, KS3)

– work on open and closed tasks in a variety of real and abstract contexts that allow them to select the mathematics to use (Maths, KS3)

Attainment Levels and Targets

In order to assess the ability of students and effectiveness of teaching, there are a set of Attainment Levels which are standard across all subjects in the curriculum. There are eight levels, plus one for ‘Exceptional Performance’. Each level has a set of Attainment Targets, which is specific to the Programme of Study. These targets define the ability and behaviour of students, so that teachers can match each pupil to the level they feel best represents their current position. These can then inform how the pupils are taught in future.

There seem to be links between targets at different levels, but the structure doesn’t seem to be especially defined here. For instance, in English (KS3), there are the following targets:

Level One: Pupils talk about matters of immediate interest.

Level Two: Pupils begin to show confidence in talking and listening, particularly where the topics interest them.

Level Three: Pupils talk and listen confidently in different contexts, exploring and communicating ideas.

Level Four: Pupils talk and listen with confidence in an increasing range of contexts.

Level Five: Pupils talk and listen confidently in a wide range of contexts, including some that are formal.

Level Six: Pupils adapt their talk to the demands of different contexts, purposes and audiences with increasing confidence.

Level Seven: Pupils are confident in matching their talk to the demands of different contexts, including those that are unfamiliar.

Level Eight: Pupils maintain and develop their talk purposefully in a range of contexts.

Exceptional Performance: Pupils select and use structures, styles and registers appropriately, adapting flexibly to a range of contexts and varying their vocabulary and expression confidently for a range of purposes and audiences.

As you can see, there’s a definite progression through this, but currently on the National Curriculum website, there’s very little structure. Here’s the Level 7 description in full. I’d say each sentence is a separate Target:

“Pupils are confident in matching their talk to the demands of different contexts, including those that are unfamiliar. They use vocabulary in precise and creative ways and organise their talk to communicate clearly. They make significant contributions to discussions, evaluating others’ ideas and varying how and when they participate. They use standard English confidently in situations that require it.”

As I mentioned in my last post, this is probably the most structured model I have found so far, but now I need to test whether it works with other curricula, and whether it has enough to be a general model for structuring formal study. Now – who wants to screen scrape the National Curriculum website to test the ontology with some data? 😉