Yesterday I spoke at Playful ’11. Thanks must go to Toby Barnes, Greg Povey and the rest of the Mudlark team for arranging the conference and inviting me to speak, and to Sarah Challis for making some animations for the slides. What follows is a blogged version of my talk, with the slides and some commentary on what I was trying to get across. There will most probably be a little ramble towards the end about some of the themes that came out of the day, too.

Simple, really – does what it says on the tin. When I first talked to Toby about speaking, I had a couple of ideas. One was more along the lines of the rest of the stuff I’ve written here – stories and making them more web-like – and the other was this. Something I’d been wanting to get off my chest for quite a while. Essentially, the frustration of seeing the huge potential of Linked Data and the Semantic Web, and being held back by the lack of tools, and what seems like the lack of willingness to produce data other than for cataloguing information, Wikipedia style.

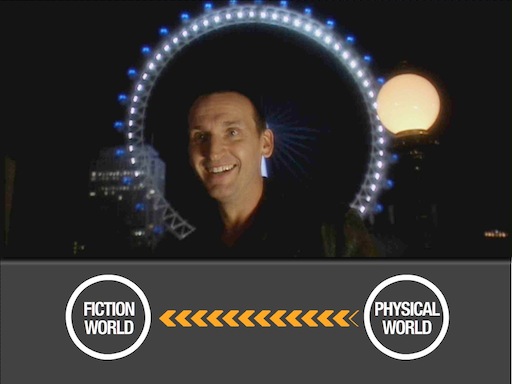

It wouldn’t be a talk of mine if it didn’t mention Doctor Who in some capacity. And since the theme of the day was nominally ‘science fiction and the future’, I thought it only proper that I should put at least one slide in on the theme. More importantly, I wanted to get across the notion that stories are information, they can be data, they can be imaginative and interesting. One of the other themes that came out of the day, which I’ll write more about towards the end of this post, was of almost a ‘failed future’, how the imaginative futures dreamed up in the sixties, seventies and eighties had, in a lot of ways, failed to appear. What was interesting from my perspective on Doctor Who, is that I don’t necessarily see it as sci-fi. Like Rachel Coldicutt, I’m rather uneasy with the stereotypical assumption of the science-fiction fan. Yes, I know I talk about Who a lot, but that’s because it’s an imaginative, thrilling, positive adventure series. I don’t expect it to be scientifically accurate. It’s the ride that counts. And that’s what I want to create more of – more adventures, more thrills. I like Doctor Who, but, aside perhaps from Star Wars (the films only), I’m not that much of a sci-fi fan. It’s fine to be one, but just as I like the Semantic Web and I can do a bit of domain modelling, that shouldn’t be what defines me. Rant (for now) over.

My talk was going to use a similar method of introducing the topic of Linked Data, but less about nostalgia. Again, growing up in what I referred to in the talk as ‘the Dark Ages’, when Doctor Who wasn’t on TV, was actually, I think, a huge advantage. I was able to see the whole thirty years of the series to date, in the space of about two years. And there was no room for nostalgia. I don’t have a favourite Doctor, or any allegiance to Sarah Jane Smith, because, unlike what seems to be the mainstream, I didn’t grow up in that era. So I don’t have the nostalgia, just the desire for more adventure. And so I wanted the talk to be more of a call to arms, an exhortation – look, we have this incredible technological concept of the Web, and yet we’re hardly using it at all – moreover, all those futures you imagined, and all the ones you’re imagining now – we can make them possible, we can make them using the conceptual framework of the Web.

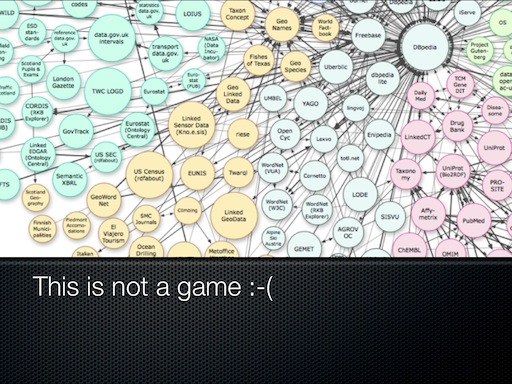

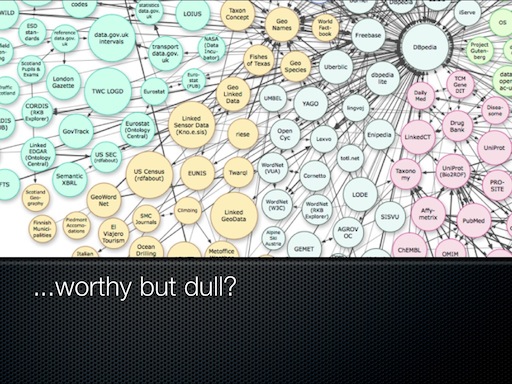

…and this was the comparison. There was a lot of talk about hardware, about real, physical toys at the conference, but I wanted to get across the point that Web data sets are equally valid as toys. They’re things we can play with. But at the moment, the vast majority of the data we’re putting online isn’t very playful at all.

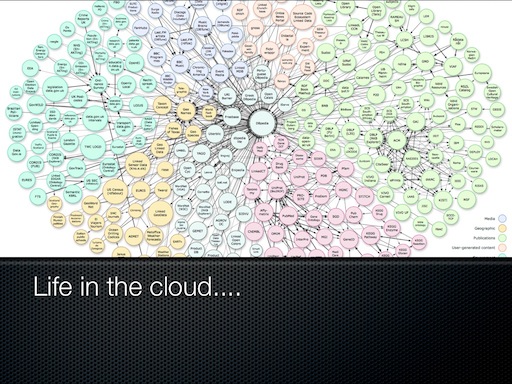

So, a traditional use of the ‘Linked Open Data’ cloud diagram. Basically to say that this is something real, something growing. It may not be the easiest thing to contribute to, or to use meaningfully at the moment, but it’s indisputably growing and if it has faults, let’s make it better.

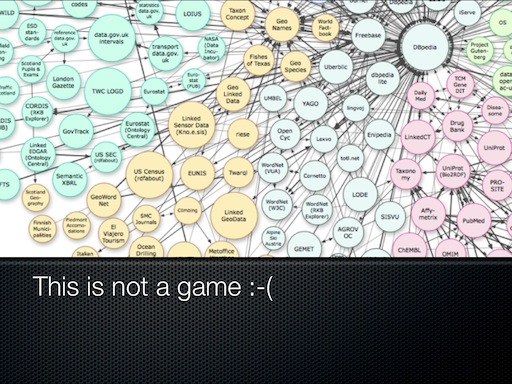

This slide originally had the full cloud diagram again, but with the word ‘BORING’ emblazoned on top. A little harsh, which is why I changed it. At heart though, it’s what I mean. I absolutely love the idea of the Semantic Web – that a URI can mean anything, and that we can use descriptive hyperlinks and URIs to represent anything in a universally accessible way. Because creative people should be able to have a field day with that. I want to see the equivalent of books, plays, radio shows, films – as Webs. Not websites. Actual informational Webs, machine readable first, which can then be rendered in what ever way we choose – with screens, through real world objects, in ways we can’t even conceive of yet. If we tie the information to a representation now, we’re hampering our ability to create a new future. Which is my way of saying what Marcus Brown said – we’re in danger of being unable to invent new futures because we constantly refer to the futures of old, we always have to couch it in those terms, we have to use existing representations, instead of dreaming up completely new ones. Now I’m being idealistic, I know – I’m perfectly happy to be pragmatic and realise that we have to deliver things that work for people right now, in ways that they understand and can use, but I do think it’s a valid argument and valid process to be both pragmatic and idealistic. I make no apology for being optimistic and wanting to dream a new future.

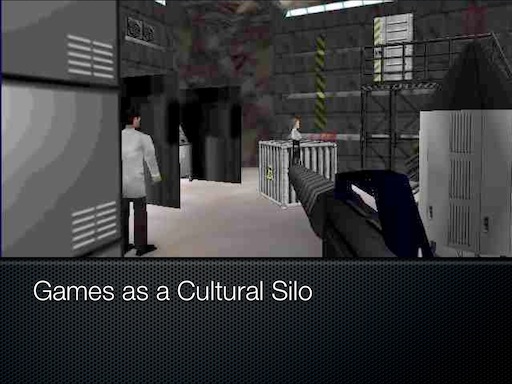

Playful has its’ roots in a conference about Game Design, so whereas normally I’d talk about the Web and stories, here I wanted to focus on games. I’m not an especially hard-core gamer, but I’m a middling one. I like the Mario games, some sports and racing ones too, a few classics like Goldeneye (more of which later…), but I’m not into things like Call of Duty or massively serious FIFA sessions, nor MMPORGS. Again, not because I dislike them in any way, just that they’ve kind of passed me by, and I’m perfectly happy with the games I grew up with. Turn based strategy, a la Civilisation II or the mid-to-late nineties versions of Championship Manager, always wins out over the more modern, real-time, intensive games, because they were about fun, not necessarily about immersion. I could never be bothered with the training mode of Championship Manager, because if you cross that line, it begins to feel more like work than play.

Once more, the quick comparison of the Linked Data Cloud to games. It’s worth noting also that I have no problem with the current publishing of Linked Data – that’s all worthy and good and should be encouraged. And I know there’s some more cultural data being published too. There’s even things like Pokemon data on there. And yet, and yet, maybe it’s just the perspective I have, but that kind of data only seems to be being released as part of a cataloguing, bibliographic, encyclopaedic exercise, and thus is very generally modelled, almost to the extent of hardly being modelled at all. I’d like to see finely crafted mini sets of data being released instead. I want a Miyamoto of Linked Data, and I don’t see why we can’t have one.

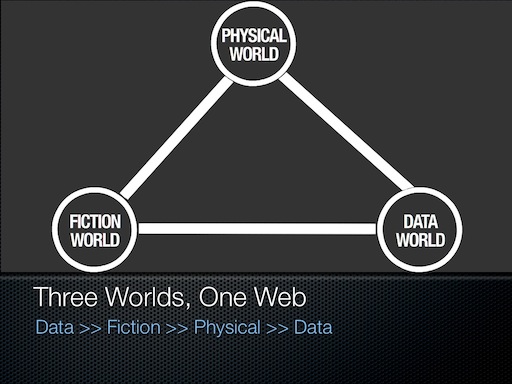

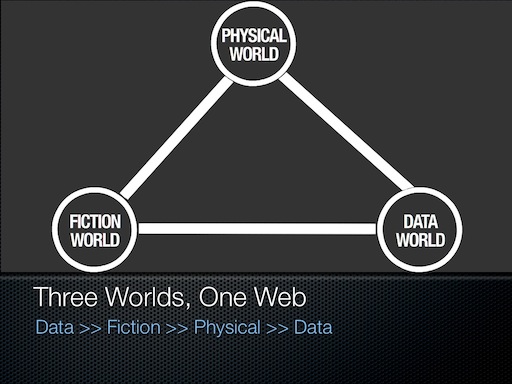

This was the central piece of the talk. Luckily, from my point of view, a few of the other talks during the day had touched on elements of this, but hadn’t explicitly called it out. Maybe it didn’t need to be, but I always find it useful to state things clearly and get some kind of conceptual model to test against what’s happening in the world. So here we have the Physical world (i.e. the real world), the Data World, i.e. the purely machine readable, informational world of the Web, and the Fictional world, the world of imagination, the one that, until now, only really exists in our minds. My main point being that the Data World gives us an opportunity to solidify and communicate imaginative ideas in a way which isn’t constrained by any existing medium or by the physical constraints of the real world. And perhaps, if ideas can be expressed in a data format, in a way which is clearly defined and expressed, does that reduce or even eliminate the noise and confusion that normally accompanies the transmission of a message through a medium? If that’s the case, what’s then possible?

Going from the Data World to the Fictional World is fairly easy – this is what’s partly behind the current vogue for ‘storytelling’ in online circles. It’s all about making sense, in our minds, of large sets of data. Bringing ’emotion’ and ‘understanding’, making ‘information’ out of data. It’s what Matt Sheret and others do at Last.fm, or, as Tom Armitage points out, what people do when they play games like Championship/Football Manager – essentially a spreadsheet of data, with an emergent story in the player’s mind.

The Fictional World can be represented in the Physical World too. Building statues to the fictional Tripods in the real world of Woking, or the Sherlock Holmes museum/house on Baker Street. I’d also include here things like ARGs and pervasive games – people making stuff up, but then it being manifested in the real world. So far, so good.

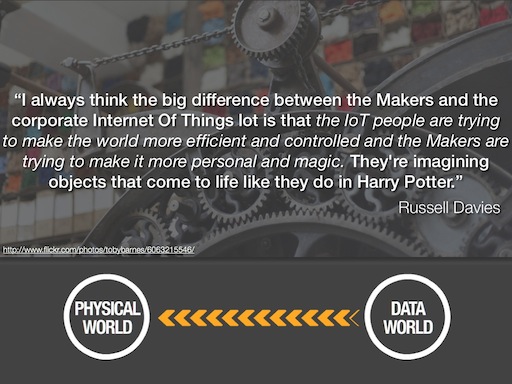

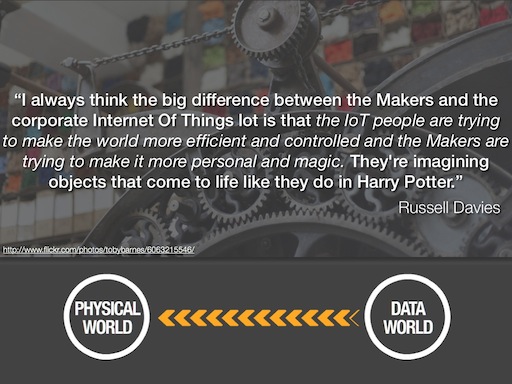

OK, so here’s where it starts to get interesting. Going from the Physical World to the Data World. Essentially, that’s what I was talking earlier about Linked Data – giving things that exist in the real world, an identity on the Web. Another side to the coin is the ‘Internet of Things’, that Russell Davies blogged about recently. That’s slightly more focused, giving objects an identity on the Web. Like Tower Bridge, or the ubiquitous Internet Fridge. And I think he sums up my point pretty well – the lack of playfulness of this movement. So here, I completely agree.

Where I’m not sure I agree so much, is when we start to go the other way around the triangle. So now, we’re moving from data to physical. This is where we take stuff on the Web, and give it some manifestation in the real world. I’m thinking things that bleep or light up when tweets are received, that kind of thing. And that’s cool. A lot of what Brendan Dawes talked about on the day was all about this kind of thing. Hardware hacking, as it’s also known. Again, I want to make clear that I’ve no real problem with it per se, but that, like the focus on the ‘futures from the 70s’, it feels very much the product of a certain group of people, those who grew up in the seventies and eighties, who were very hands on with electronics and technology. I did those classes at school too, and whilst I’m not useless with a hacksaw or soldering iron, it just doesn’t hold the same allure for me. I feel a bit bad about this, but it just doesn’t (excuse the pun) push any buttons for me. What does, instead, is the Web – because conceptually it’s not limited by physical constraints. And, coming from a humanities background, once you understand the basics of the triple patten (subject, predicate, object), you can create almost anything – it becomes easy. So whilst we should continue to hack with hardware, and be influenced by the futures we grew up with as children, I find it difficult to feel moved or excited by that.

Another easy one – things in the real world can inspire, or find their way into fiction. Another Doctor Who example, here, but Naomi Alderman also pointed out that the Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling, are an equally valid example of this.

All of which then begs the question – if there’s ways of going from Data to Fiction, from Fiction to Physical, and from Physical to Data, and back the other way, why aren’t we doing more of going from Fiction to the Data world? I think it’s at least worth a try, and the rest of the talk discussed some elements of the implications of this.

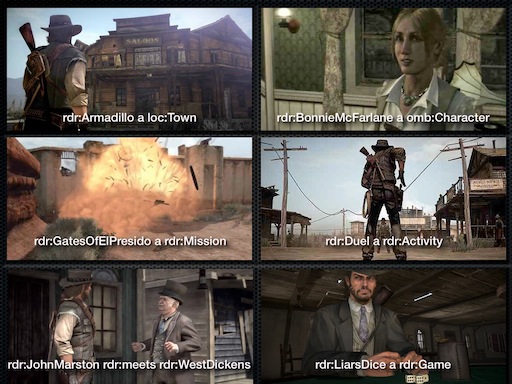

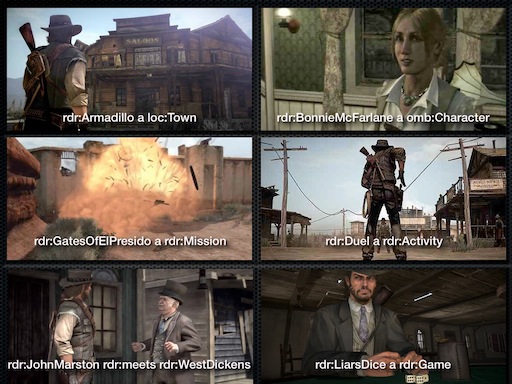

The first example I used was Red Dead Redemption, primarily because having played it through the summer this year, I feel it really succeeded in creating an immersive and also fun world to explore and play around in. Here, I wanted to explore ways in which we could move from fiction to data. Simply put, this would be about identifying various aspects of the game – the characters the locations, the missions etc. and linking them together. Making games more atomic, as Dan Biddle has suggested for television. Again, I know things out there like Wikia allow you to do this kind of thing to some extent, but perhaps it’s just the front end which I’m not inspired by – it’s done from the point of view of an encyclopedia, whereas I think there’s other possible ways of representing that data.

The second example I used was the Mario universe. Here, I showed six different representations of Princess Peach’s castle, as it appears in six different games. But of course, in the player’s mind, if they play more than one of these games, it’s the same castle. So those games should be linked together, not just in the minds of people playing them, but in a data way too. I don’t know exactly where this would lead us, but at the moment when we talk of ‘networked games’, we tend to mean players playing at the same time, using the Internet as a distribution mechanism. What if the games themselves were networked, so you could travel between games in one coherent universe?

Going back to the idea of ‘atomising’ cultural artefacts – the focus on the finished product is all well and good, and we should still give people that, but why not also give them the whole package of information to blend and mix and link to/from as well? Again, it gives us the flexibility to rework and build upon those products in the future. Just as you can take apart a piece of hardware and use a tiny bit of it in something else, why not do the same with a game? In the context of video or audio, I don’t just mean a temporal portion of the medium, but the actual concepts within them. Here I used the example of the Goldeneye 007 game – which I love. This level, Silo, is a level which doesn’t appear in the film. But we know the film exists too – what if you could blend the film and the game together?

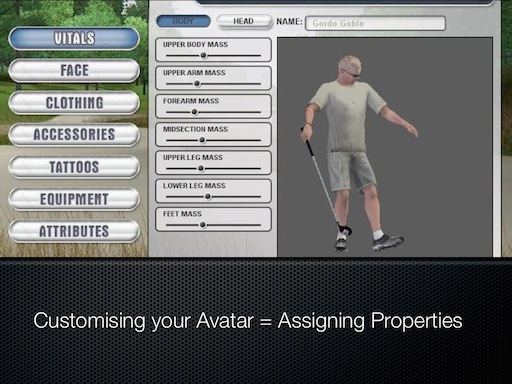

Part of the criticism levelled at Semantic Web technologies right now is the lack of decent tools. So this slide was just trying to point out that in the context of games, there are some similar concepts. Customising or building a character, is essentially the same as creating a URI and assigning properties to it.

Similarly, Minecraft is a game all about resources – finding them, combining them, creating them and constructing beautiful new things out of them. The Web, and especially the Linked Data Web, is the same – it’s all resources, and now we need to empower people not just to consume them, but to play with and create new things from them. Here’s where I’d also like to reference Mozilla’s Web Makers initiative, as I think it’s trying to encourage people along the same lines.

Into the home stretch now – in Steven Johnson’s book ‘Where Good Ideas Come From’, he talks about the idea of the Adjacent Possible – that ideas can come from anywhere, but only certain ideas can be manifested depending on the environment – so Charles Babbage was able to come up with the idea for the computer, but the technology he had to hand didn’t make it practical. And I guess this is where I want to be positive about the Semantic Web too. It sometimes feels as if these ideas were considered ‘right’ in about 2005-2008, but then it was tried and it failed. Which is a real shame, because those experiments were exactly what inspired me in my career to date. The point I want to make is that we shouldn’t dismiss Linked Data as a failed thing just yet. Whilst I’m not trying to claim that it’s the perfect solution, I just want us to keep experimenting – because the more we do that, the more likely it is that we’ll create the future that does make it viable.

So finally, a couple of quotes from people I really admire – Tim Wright is up first – he talks about not leaving space exploration to the professionals. Well, I don’t think we should necessarily leave the Semantic Web to the academics, scientists and governments. The Web grew not because people were doing it absolutely correctly, but because they were trying things out. And they were doing so with stuff that was interesting to them, and crucially, stuff which was mainstream and interesting to others. So let’s do the same. Let’s not just have academic, scientific, political and encyclopaedic data – let’s have fun, playful data.

Because for all our talk nowadays of passive, lean back experiences, I think we deserve more. I think on some level, we want to wallow, we want to get lost – we want to get vertigo when we lean into the device.

And that’s about it. Phew, that was a long one. But ultimately I think there’s room for positivity, room to experiment with Linked Data, and to create the futures of the future. Soon, I’ll blog about the rest of the Playful conference (much shorter!) and an idea (possibly impractical) for a slightly different format of conference.